Artists see things first

At the risk of undermining the very argument we wish to put to you at Horasis lets begin with a quote from Dominic Cummings, the man behind Brexit, Boris Johnson’s special advisor. Cummings may slightly exaggerate our point but he makes it succinctly: ‘A very interesting comment that I have heard from some of the most important scientists involved in the creation of advanced technologies is that ‘artists see things first’ — that is, artists glimpse possibilities before most technologists and long before most businessmen and politicians.’ For Horasis ‘the Glossary team’ have compiled a glossary of words frequently used by the arts and business world to show how art and business are much more interconnected than people think. A recent trip to see the work of Turkish artist Hale Tenger shows how artists can flag up inventions and trends way before the rest of society catches up.

Instagram stories, snapchat, and other forms of communication that flash up at you and then disappear have their roots in art that was pioneered back in the 1970s and 80s in countries such as Russia, where holding contradictory thoughts in your head was an essential form of survival. The Moscow Conceptualists made this into an art form, but as this double thinking has become main stream. Hale Tenger is one of its leading practitioners in Turkey. She is a survivor because of it. In her recent Istanbul exhibition based on a poem by Edip Cansever there was a dark pool of oil out of which came two lines of the poem. It writes: ‘We didn’t pull the body out from underwater.’ The words then submerge and a little later another monstrous line appears from the deep. It contradicts the earlier line: ‘We had pulled the body out from underwater.’

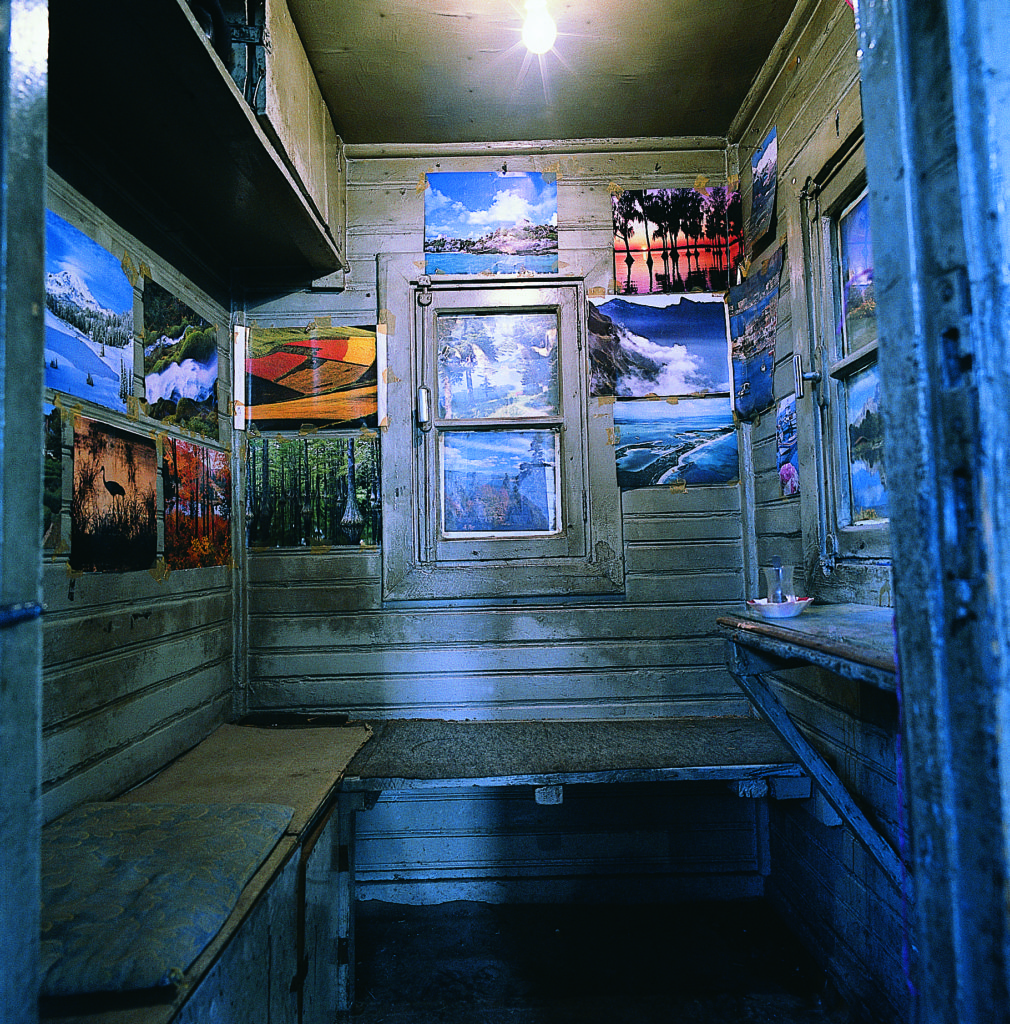

Keep out! We didn’t go outside; we were always on the outside/we didn’t go inside; we were always on the inside, 1995, by Hale Tenger

Tenger’s work appears very much of the moment. It chimes with the way teenagers want their messages to seduce one moment but disappear before the morning hangover. Tenger was tuning this concept in the 1990s when her work was shown in the third and fourth Istanbul Biennials of 1992 and 1995. Her work in 1995 is probably her most famous, We didn’t go outside; we were always on the outside/we didn’t go inside; we were always on the inside, 1995. The title is taken again from Edip Cansever. Note again the contradictory thoughts held in the words but in this case also the visuals. The work consists of an old abandoned customs hut she discovered on the harbour site of the Biennale. She simply put a barbed wire fence around it, which made visitors to the art event unsure whether they were allowed to go in or not. Those brave enough to venture first through the perimeter and then into the ex-den of the guards found a mini-exhibition of chintzy posters, calendar pin-ups, pretty posters and photographs. The Antrepo customs post had originally been on the second floor, so by putting calendars and posters over the windows it was as if they were intentionally blocking out one of the most spectacular and sought-after views over the Bosphorus to the Golden Horn. Those ‘always on the outside’ might assume that the postcard view was what art was about. Other visitors might question whether it is possible to be a complete insider or total outsider. At no one point as one walks in and out can you take in the whole experience. It is ostensibly the perfect illustration of the Either/Or situation.

With the flood of images and text coming through our screens coming ever faster, most of us today are quite used to the disfunction between words and content. Hale Tenger is challenging the results of the educational, legal and constitutional systems of most countries being based on good old-fashioned straight male thinking. Yet, even if they don’t know it, most young people have abandoned this. We are used to doubting what we read, and indeed what we see. There are a few young people who are prepared to sign up to believing one simple message, one system of thinking. There is no turning back the flow of rich, contradictory information, philosophies and strategies. Tenger illustrates how the Capitalist world presents, markets and brands products and services by the extremities of the inside and out. We are growing bored of such a simplistic model of how we think. We are not binary. Artists Hale Tenger and the Moscow Conceptualists were among the first to recognise this and offer ways of changing. Tenger’s artistic statement on Galleri Nev Istanbul’s website says her interest is in ‘civilisation and progress.’

‘But surely you don’t believe in Civilisation and Progress?’ I ask

Her smile says ‘hell no.’

‘You believe in change? You have helped change the world,’ I persist.

‘Change is too ambitious,’ she says. ‘Maybe I can add a little drop in the Ocean.’

Keep in! We didn’t go outside; we were always on the outside/we didn’t go inside; we were always on the inside, 1995, by Hale Tenger

This article was authored by Alistair Hicks, Global Art Compass, United Kingdom. Alistair Hicks was in Turkey researching his upcoming book on Istanbuller artists.