Does globalization have to mean massive inequality? Maybe not — there’s a better way

This article was originally published on Salon by Horasis Chairman Frank-Jürgen Richter

If globalization remains a nebulous concept, its negative repercussions may today seem more plain than ever. From Brexit to Trump, to Viktor Orbán’s recent victory in Hungary, a deep-seated resentment of globalization is boiling over worldwide. And with the alarming resurgence of populism and protectionism, everybody is once more reprising the old arguments, weighing globalization’s benefits against its ills.

For its critics, the recently released World Inequality Report validated the bleaker version of the globalization narrative. According to this narrative, inequality is an inevitable outcome of globalization. And since 1980, the report confirms, inequality between the world’s citizens has grown.

But while many will leverage the report to flatly reject what is an irreversible global phenomenon, the data doesn’t easily permit such unproductive resignation. As a recent piece in the Harvard Business Review points out, the report also helps to dispel a pervasive misperception about globalization, and in doing so invites the sort of productive dialogue that today is so desperately needed.

Contrary to what’s commonly believed, the report’s numbers indicate that inequality is not the inevitable companion of increased trade and technology, but rather the result of policy. For instance, when comparing changes in equality in the U.S. and Europe since 1980, the United States’ comparatively much larger increase in inequality can be traced to America’s decisions in key policy areas concerning inequality – the undermining of the income tax, the cost of higher education, a grievously outdated minimum wage and the denial of universal health care.

It is long past time to move beyond rehashing the pros and cons and commit ourselves to solution-driven discussions aimed at a more egalitarian globalization. International trade, digitalization, capital flows and mass communication have generated big winners and losers: unprecedented progress and prosperity, as well as frustration and fear. We are not, however, helpless to make globalization work for the masses, nor must our politics be steered by fear or complacency. And among the many steps to be taken, a few stand out as critical.

Breaking the cycle of short-termism

For starters, fundamental to aspiring towards a more morally decent form of globalization is a commitment to farsighted governance. To the detriment of long-term outcomes, our leaders frequently opt for the immediately popular and most painless plan over big-picture-oriented policy; they postpone the “hard calls” up until the point at which those options are no longer available. And as Jonathan Boston has argued, in the hyper-connected digital age this tendency is exacerbated by media pressures and public expectations of an immediate response to events.

To a great extent, this short-termism can be attributed to the imperatives of short electoral cycles – especially in the West, policy-makers don’t serve long enough terms to tackle complex social and economic issues. They are instead often concerned with pleasing the populace in the time they have, for the sake of leaving their mark or for re-election. A first step towards embedding farsighted governance would be lengthening electoral terms. Here we might look to the more virtuous aspects of Eastern political systems like those of Singapore and China.

Though the West may frown upon some aspects of the Chinese political system, at the highest meritocratic levels of Chinese government leaders serve 10-year terms and decisions are made with future generations in mind. While China is investing billions in a forward-thinking “new Silk Road,” U.S. underinvestment in infrastructure is costing the American family $3,400 a year.

Future-focused thinking can begin to rectify and reverse the perverse effects of globalism and increasing inequality. The financial crisis, for example, hit the middle and lower classes especially hard, while the environmental cost of globalization has been disproportionately paid by the poor. Even still, political myopia continues to thwart both regulation to stave off another financial crisis and measures to avert climate catastrophe.

Strengthening multinational institutions

As Brexit and growing anti-EU sentiment can attest, trust in international bodies is at a low – fear of globalization has fed populism, and populists portray multinational institutions as a threat to national sovereignty. And yet, it is international, multi-stakeholder approaches to policy-making that are essential to undermining shortsighted governance and ensuring that the fruits of globalization are more evenly distributed.

Unilateral governance is by nature narrow-minded and self-serving. Meanwhile, the potential of collaborative policy forums to ensure globally equitable governance is as great as its collective, international buy-in.

At their best, international organizations have achieved feats that would have proven impossible by means of go-it-alone governance. The recently much maligned EU, for one, deserves credit for securing the longest lasting peace Europe has known in more than 2,000 years. Dedicated to the principle that sharing wealth can accelerate growth, its stewardship has brought stability and prosperity to both the peripheral and strong economies of member states.

In the face of growing isolationism, the world’s leaders must recommit to multilateral governance ensuring fair trade, safeguarding human rights and promoting just social policies. And through active participation, we should hold these bodies to higher standards.

Providing for the powerless

Social welfare systems, many of which originated in the Industrial Revolution, have not kept pace with globalization. With millions of jobs transferred from developed to lower-cost countries, and the persistent threat of outsourcing, a culture of anxiety and anger has gripped much of the middle and lower classes. It is from this economic instability and fear that populism and its counterproductive policies draw support.

As we work towards a fair globalization, we must also correct for its unjust ramifications, returning confidence to those who feel forgotten and powerless in its wake. To do so, we must introduce progressive social welfare policies, in particular, universal health care and legislation raising the minimum wage to reflect costs of living.

According to the World Health Organization, paying out of pocket for health services pushes 100 million people below the poverty line, while increased health care coverage improves health indicators, contributes to economic growth and reduces poverty. The overall economic effect of raising the minimum wage, meanwhile, is endlessly disputed – but there is a consensus that it lowers the number of people living in poverty.

As a society, we have the moral obligation to protect those who do not have the resources to protect themselves. And to that moral justification we can add a pragmatic rationale: Economic stability for the masses fosters political stability, and undermines fear-based politics.

A moral, sustainable globalization

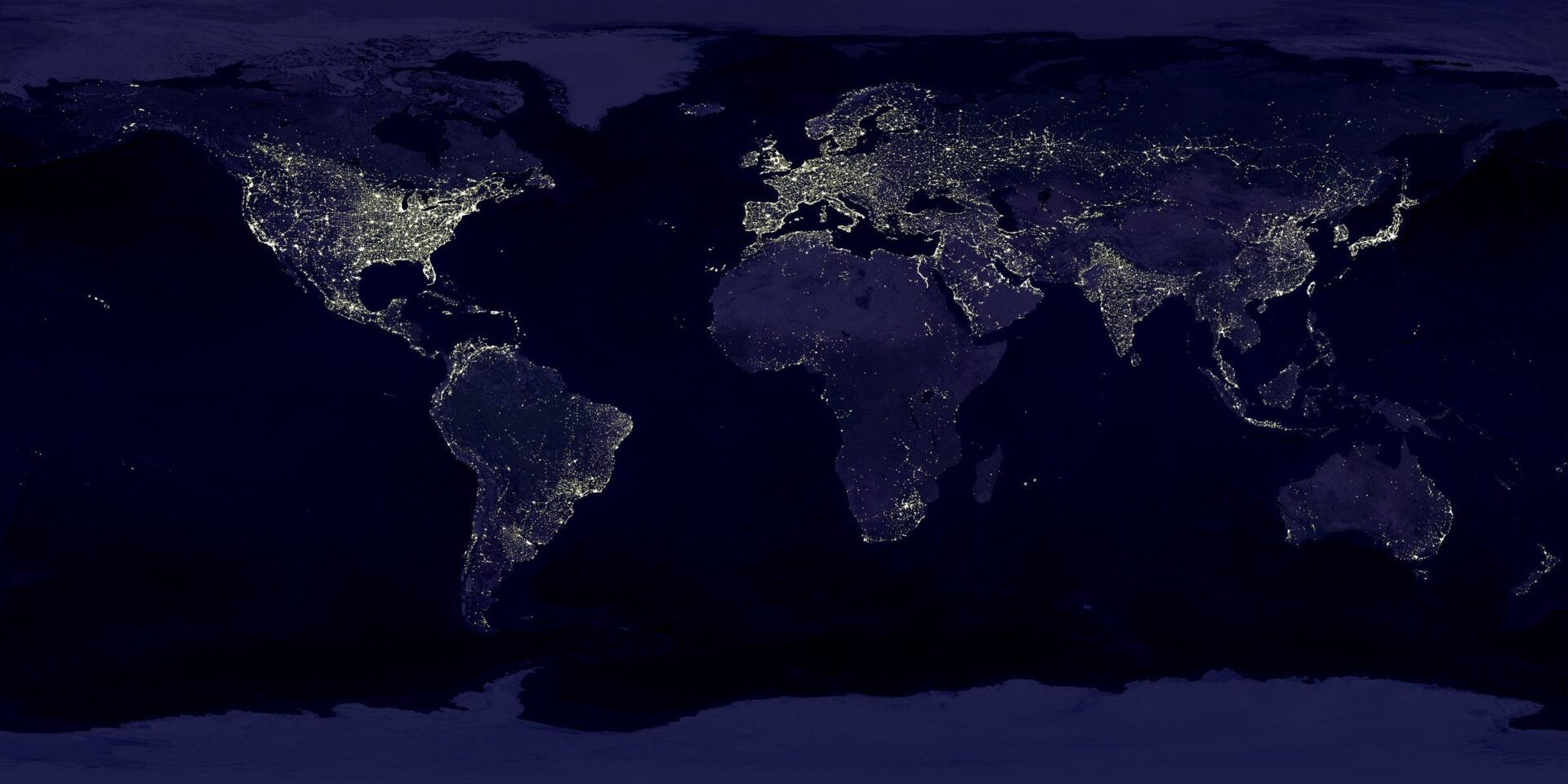

Over three and a half decades, globalization has rapidly transformed industries and economies worldwide. It has brought jobs to developing nations, facilitated cross-cultural exchanges and the transfer of technical know-how and in some ways created conditions ripe for democracy. But policy has not kept pace, and today a great portion of the world perceives themselves to be globalization’s losers.

We now require a new modus operandi that restores people’s faith in the idea of an egalitarian globalization, and one that makes good on those promises. Going forward, complacency will be no more sustainable than emotion-based politics.