Managing Chaos: Weighing International Responses to a Pandemic

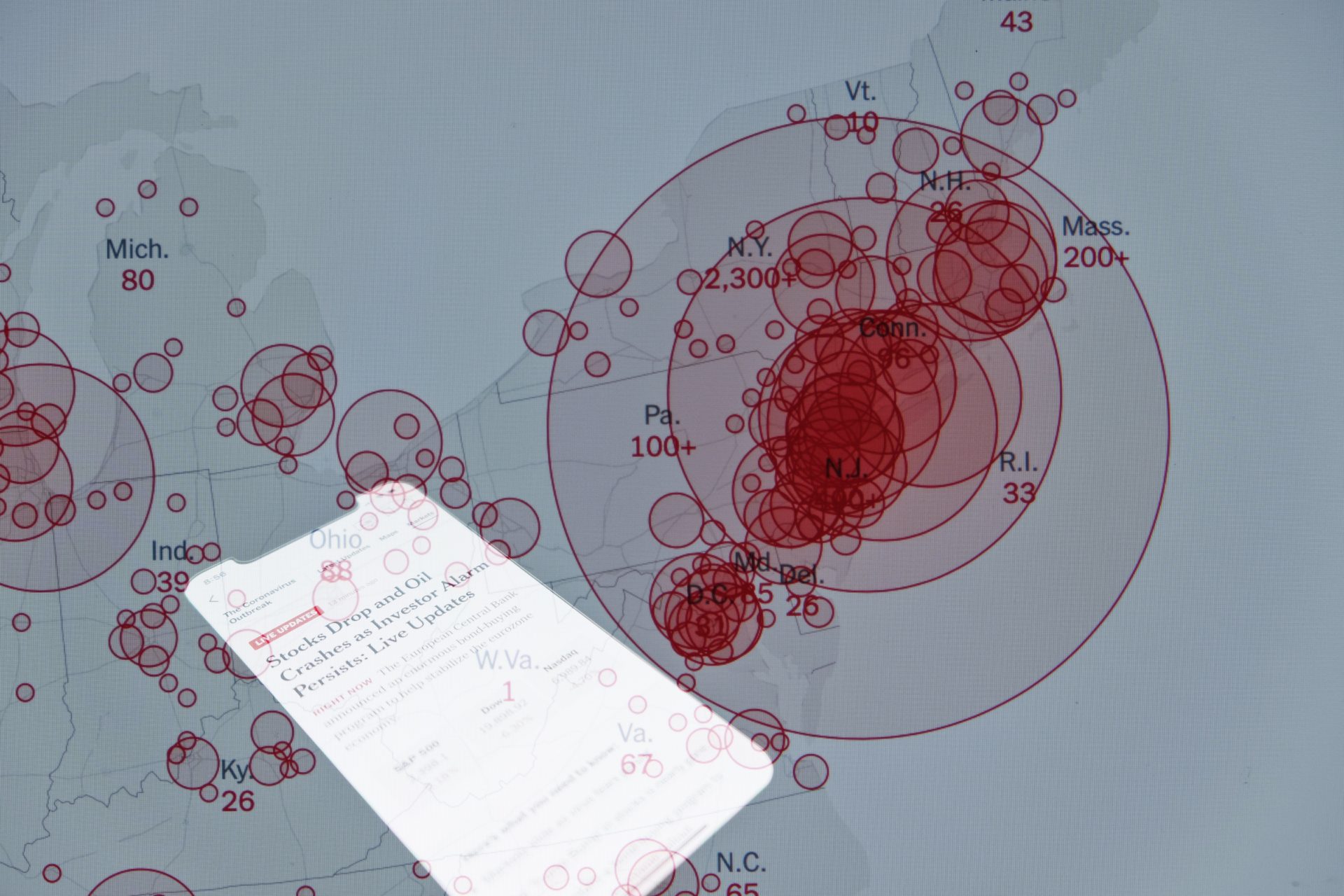

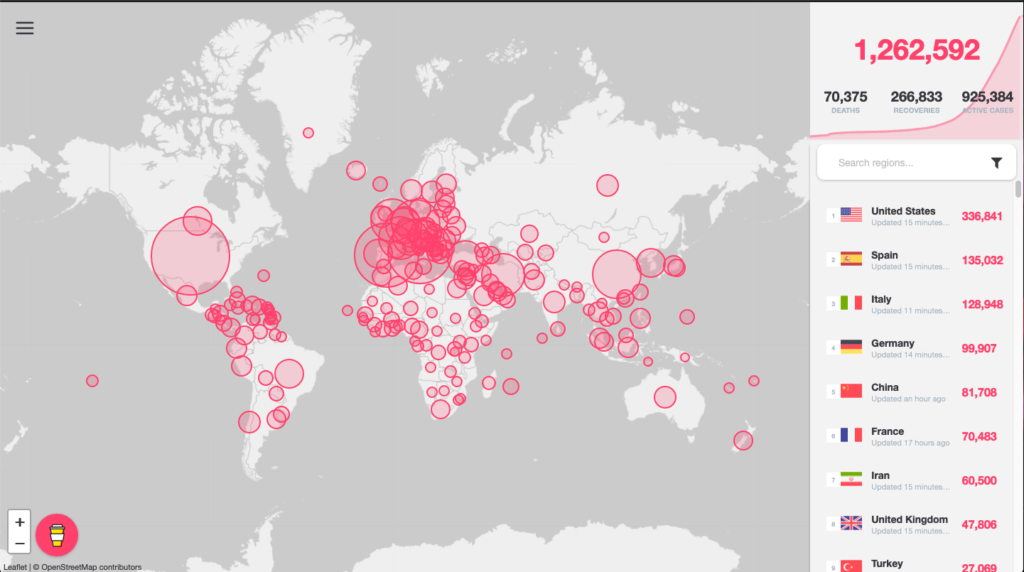

Worldwide, 209 countries and territories have reported cases of COVID-19.

The virus ping ponged in a globalised fashion between China, Italy, South Korea and the rest of the world. Receiving the ball at different times, the rigorous lock-down approach the Chinese Wuhan region was subjected to in January has not been replicated by Western democracies when the virus entered their communities. The world has a shared priority: stopping the spread of COVID-19 to save lives. But, although the what is clear, governments differ on the how. Direct and indirect consequences are diverse and complex. For example, what economic costs are justified in such times? When resources are scarce, who “deserves” treatment? How to weigh the rights of an individual against the rights of the collective? Faced with an invisible enemy, governments have turned to data. Why does data matter in a pandemic? Looking at both the East and West, this article explains how data grants governments 1) visibility to 2) assert control.

The East

Starting with the end in mind, what do governments hope to achieve by collecting data? Turning towards the East first, we will briefly travel through governmental responses of Singapore, South Korea, Hong Kong and China.

Singapore made “contact tracing” a pillar in fighting COVID-19. Using Bluetooth technology, the government app TraceTogether logs all who have been within two meters of each other for longer than 30 minutes. Although the app is offered on a voluntary opt-in basis, refusal to give consent could warrant prosecution under Singapore’s Infectious Disease Act. Data sharing opt-in policy is even less discretionary in South Korea. Here, smartphones buzz with corona alerts. A typical alert might read: “A man in his 70s just tested positive,” adding a link to a list of recent places the infected individual has visited. This log is based on location data and sometimes even credit card transactions. Although only gender, age range and case number are revealed, names of shops and restaurants are specified. The Guardian reports that South Korean TV-reporters managed to track down a woman who claimed to be recently hospitalised by a car accident, but who, outed by the app, continued to visit restaurants and weddings, to ask her to comment on insurance fraud accusations. If tested positive, South Koreans risk broadcasting their private lives publicly. Hong Kong takes its data policy a step further still. In Hong Kong, location data is used to find and fine those who break mandated quarantine. “The right to life refers not only to the right of life of the data subject, but also to the right to life of others in society.”, the Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data commented.

Following consent coercion in Singapore, public shaming in South Korea, and automated judgement in Hong Kong, China has made data sharing contingent on human rights, specifically the right of freedom of movement. An add-on to the WeChat messaging giant, the Alipay health app generates bar codes in three colours: green, yellow and red. A green bar code is required for access to services such as public transport, a yellow score requires a seven day stretch of self-isolation, and a red colour demands a two-week isolation period, which could include self-quarantine or a supervised variant. But how is this score composed?

The underlying premise is a real-time contact mapping network. This is how it works. The New York Times reports a mix of self-entered information (e.g. name, national identity number, and known patient contact), supplemented by real-time location data (GPS), proximity sensing between phones (Bluetooth), and QR code scanning at entrance and exit points of public gatherings (manual). A closed algorithm continuously processes this information to create a new barcode every 24-hours. Meanwhile, it appears that this data is shared with a government hosted server, suggesting law enforcement access. The app is expected to roll-out widely as retail and restaurants adopt the green QR code requirement. The result is private data, processed in private calculations, with personal consequences, shared with unspecified third parties.

In the East, data is captured centrally, and apps are used to control who can re-enter society as it reboots.

The West

Like in the East, Western countries such as the US, the UK, Italy and Germany, also view data as a powerful tool to gain visibility on the spread of COVID-19, with the goal to ultimately better control it. Even GDPR advocating Europe seems to sway away from privacy in favour of data asserted control. However, where centralised governmental data access defined the Eastern approach, the Western approach is characterised by private companies.

American technology giants such as Google have publicly committed to repurpose user data for resource deployment insights. In Google’s case specifically, this constitutes of aggregated, anonymised data tracing physical movement over time split by geography across high-level sub-categories, such as the “Retail & Recreation” category depicted below. Users from 131 countries who have location sharing settings turned on are included in the dataset. Notably, this information is not real-time (i.e. data represents 48-to-72 hours prior, arguably sacrificing efficiency in favour of privacy) and treated with a de-identification technique called differential privacy (mathematically introducing noise).

As the US turns to Silicon Valley, in the UK and Italy European telecommunications companies are the preferred partner. British Telecom is reportedly in talks with the UK government about leveraging its EE location usage data on an anonymised basis with a 12-24-hour delay. Using a combination of the telecom arsenal, including Bluetooth beacons, Wi-Fi towers, GPS, and more, such reach can be considered comprehensive. The data is said to be deleted afterwards, but no firm timeframe has been specified. Similar to the UK’s collaboration with BT, Italy is working with Vodafone on its own location mapping initiative. In contrast to the Brexiting UK, Italy is firmly placed within GDPR jurisdiction. However, after announcing a national emergency, the fine print stated that some GDPR principles in Italy have been suspended until at least 30 July 2020. GDPR Article 9 allows for such suspension in times of crisis. North of Italy, Germany is working on a Singapore-style contact tracing app. The voluntary app is planned to record proximity and duration of contact on an anonymous basis, saved for a period of two weeks. To date, EU-wide coordination is lacking, with Germany, Austria, The Netherlands, Ireland and Poland among the countries introducing some variant of contact tracing apps.

In the West, where data is less concentrated than in the East, the threat of COVID-19 sees the full reach and impact of the private data capturing infrastructure exposed.

Privacy Is Suspended

One would expect differing attitudes towards privacy in the East and West of the world, but the last few weeks have showed that the deterioration of privacy is in fact global. Whereas governments in the East tap into existing centralised data infrastructure, in other words turn existing surveillance towards a different subject, the West activates private infrastructure via its governments, as evidenced by Google in the US, BT in the UK and Vodafone in Italy. If privacy is suspended, until when is this the case? And, once lost, will it ever come back?

The morality of it all is contingent to big, contentious assumptions. One of these assumptions is that location data can be successfully anonymised, a claim which is heavily contested. Another assumption is that the end justifies the means, falling into utilitarian style reasoning; the greatest good for the greatest number. Yet two traditional objectives to utilitarianism is that it fails to respect individual rights, and that it is not possible to consider all benefits, for not all benefits are easily quantifiable. Privacy among them. This is not a theoretical exercise gaining nuance and depth with time, instead this new reality, our new reality, demand speed and accuracy in the same breath. In the fog of war morality is hard to assess. As data is indeed essential to better manage the unfolding pandemic in the short-term, but privacy is a precursor to human rights in the long-term, I propose five ways to measure privacy in a pandemic.

- Identification: Anonymised Aggregation (Best Practise) vs. Exclusive Identification (Red Flag)

- Timeliness: Delayed Reporting (Best Practise) vs. Real-Time Reporting (Red Flag)

- Data Storage: Temporary (Best Practise) vs. Permanent (Red Flag)

- Consent: Voluntary Opt-In (Best Practise) vs. Mandatory Opt-In (Red Flag)

- Purpose: Collective-Level Resource Deployment (Best Practise) vs. Individual-Level Restrictions (Red Flag)

In sum, data should be logged on a transparent and voluntary basis, treated with privacy preserving techniques to arrive at an anonymised aggregated dataset, used for the specific purpose of better resource deployment for the entire citizenry, and which is deleted after meeting its goal. Other best practises for governments include independent oversight to data collection practises, legislatively guaranteed equitable treatment, auditability of algorithms, and, most importantly, revoking extenuating permissions when the extenuating circumstances end.

We have seen that data concentration is positively correlated with decision and implementation speed. We also found that the tension between a collective and individual cultural focus manifested itself in the ranking of human rights vs. national priorities.

The 8-billion-lives question is this: how to create the conditions where people would willingly and gladly share data, whilst rewarding this trust in kind. Leadership across a whole range of different disciplines is needed. Not just the medical staff on the front line, and the science experts working around the clock to develop vaccines, but also economic, data and privacy expertise and leadership, to ensure that what is left is worth it. Don’t let the future right to privacy be among the casualties.

_

Arwen Smit specialises in technology ethics and its intended and unintended consequences on society. Smit is the author of Identity Reboot, a book examining how the break-down of personal data privacy is being exploited from profit and power perspectives, arguing that human behaviour is being devalued to an optimisation game, and that we are providing the data that will be optimised for. Smit is a mentor at the Web 3.0 accelerator Outlier Ventures and an expert advisor to the European Commission.