To Ask The Right Question. First Steps In Restoring The American Republic

“Man cannot receive an answer to a question he has not asked.”

Paul Tillich, The Courage to Be (1952)

In the crushing final days of Donald Trump’s presidency, American laws and democratic institutions were attacked at previously unimaginable levels. Yet, in the time since the January 6, 2021 insurrection, the nation’s principal political leaders have merely tinkered at the edges of what is genuinely important. Still preoccupied with narrowly partisan and often demeaning goals – with Platonic “shadows” of reality – “We the people” have remained substantially indifferent to any reason-based queries.

Is this conspicuous indifference a result of deficient citizen intellects or are Americans simply unable to muster the personal courage needed for serious analytic thought? Whatever the answer, one response lies beyond any meaningful challenge: However well intentioned, informed, or “improved,” no proposed presidential or political directives can ever do more than reflect the American nation’s deepest human inclinations.

Though frequently misunderstood, there is far more to the United States Constitution than disjointed affirmations of second amendment rights. This very same observation about Constitutional meanings can be offered more generally about America’s philosophic underpinnings. These foundational principles were conceived with a view toward maximizing national security and “domestic tranquility.” Their cumulative intent was a sovereign nation-state able to protect itself in an “everyone for himself” world of international anarchy, but not to rely upon “self-help” measures or vigilantism within the United States.

In its domestic or intranational expressions, the American republic was never fashioned upon premises of individual “self-defense.”

Following Plato’s Republic, which was well-known to America’s Constitutional Founders, politics (all politics) is best understood as “shadow.”[1][1] While it remains plausible to expect variously tangible increments of progress from selected statutes, legislation and institutions, nothing in such increments could expectedly ease the ever-growing pain of America’s “lonely crowd.” Accordingly, still driven by competitive self-centeredness and by palpably raw commerce, the imperiled American republic’s system of rational governance has recently reached a most worrisome nadir.

Ironically, at least from the standpoint of its contrary juxtapositions, this system has already managed to spawn a paradoxical amalgam of gilded plutocracy and mob rule.

Going forward, any realistic hoped-for rescues of the American Republic must be sought far beyond the reflective secondary spheres of government and politics. Always, by definition, such rescues must begin with the individual citizen. But as long as this “microcosm” is animated more by acrimony than by rational cooperation, the “macrocosm” will remain incapable of rendering any significant national improvements.

Correspondingly, the individual citizen, the microcosm, will remain detached, dissembling and more-or-less discontented. It will be a “know nothing” time of once foreseeable lamentations.

“The crowd,” warned Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, “is untruth.” Within the rancorous American crowd (Sigmund Freud would have called it a “horde,” Friedrich Nietzsche a “herd” and Carl G. Jung a “mass”), loudly proclaimed differences remain utterly beside the point. In essence. no purposeful US national renewal (let alone any promised “greatness”) can originate from politics.

Always, political behavior, whether discernibly welcome or unwelcome, is only just reflection.

There is ample pertinent detail. Every nation-state comes to mirror the sum total of its constituent “souls.” And these individuals, seeking some form or other of “redemption,” ought never expect to be “healed” by any group-centered imitativeness or by amusement-directed mass taste. Before there can ever take place any genuine mending of the American Republic, there must first take place a suitable transformation of its beleaguered citizenry.

There is more. It’s time for candor. At best, the “life of the mind” in the United States has become discernibly tenuous.

There are variously identifiable reasons. Again and again, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s advice that Americans should seek “plain living and high thinking” has been turned on its head. Despite reasonable calls from respectable quarters for “diversity,” on critical matters of much deeper significance, this country’s national landscape is now patently homogeneous. With precious few exceptions, America’s assorted creeds display near-uniform hostility to utterly indispensable considerations of intellect or “mind.”

The disintegrative result is already plain for all to see.

For the moment, whatever policies are being decided in politics, Americans are being carried forth not by any nobilities of “high thinking and plain living,” but by sorrowful eruptions of fear and agitation. At times, “We the people” may even wish to slow down a bit and “smell the roses,” but our battered and battering country will likely impose or re-impose the merciless rhythms of a greedily-destructive machine. Inter alia, the reasonably expected end of all such breathless delirium could keep Americans from remembering who they once were and who they might once still have become.

If politics can never save the United States, where instead shall this nation turn? What, if anything, can be done to escape the pendulum of its own mad national clockwork? Americans habitually pay lip service to the Declaration and the Constitution, but almost no one authentically cares about (or reads) these musty old documents. Generally invoked only for surface effect or ostentation, the legal and philosophical foundations of the United States have become the insignificant province of a largely irrelevant minority.

It didn’t have to be this way. Americans, in fact, inhabit the one society that could have been different. Once, they possessed a commendably unique potential to nurture individuals to become more than just cogs in some compliant “crowd.” Emerson once even described us as a people guided by auspicious combinations of personal industry and “self-reliance.”

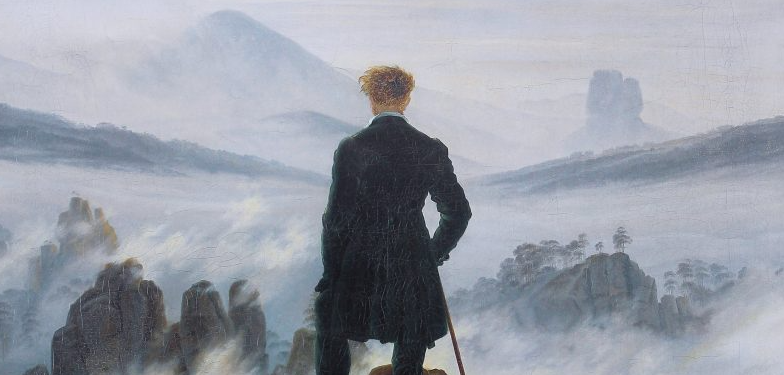

Presently, America’s true national motivators lie in “fitting in,” in tirades of bitter anger, and (even without any prior knowledge of the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard) “fear and trembling.” “I celebrate myself, and sing myself,” said the American poet Walt Whitman, but today the nation’s “self” remains under steady “assault” by a proudly rancorous mediocrity. By definition, the Horde, or Herd, or Mass, or Crowd can never actually become few. Still, some individual members of the state can make a very difficult transformation. “One must become accustomed to living on mountains,” says the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, “to seeing the wretched ephemeral chatter of politics and national egotism beneath one.”

In the end, credulity remains America’s worst enemy. Our all-too-willing inclination to believe that personal and societal redemption can lie in politics describes a potentially fatal disorder. Many critical social and economic issues do need to be addressed further by national government, but so too must America’s core problems be solved at a microcosmic or individual human level.

It’s high time to ask the right question: How shall Americans best prepare to survive, as citizens, as a nation and as interrelated beings on an increasingly imperiled planet? Unless we can finally ask this primal question, the Republic will continue to teeter on variously shifting and unsteady foundations. Recalling 20th century American philosopher Paul Tillich’s counsel that the individual “cannot receive an answer to a question he has not asked,” no proposed question could possibly prove more patriotic.

[1][1] See by this author at Horasis (Zurich): Louis René Beres, https://horasis.org/looking-

———————–

LOUIS RENÉ BERES was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971) and is author of many books and articles dealing with literature, art, philosophy, international relations and international law. His writings on American life and thought have been published in Yale Global Online; Harvard National Security Journal; Oxford University Press; Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists; The Daily Princetonian; US News & World Report; The Hill; Horasis (Zurich); The Hudson Review; Michigan Quarterly Review; The New York Times; Dissent; The National Interest; and The Atlantic. Professor Beres’ twelfth book, Surviving Amid Chaos: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy, was published in 2016 by Rowman & Littlefield (2nd edition, 2018). https://paw.princeton.edu/new-books/surviving-amid-chaos-israel%E2%80%99s-nuclear-strategy He was born in Zürich, Switzerland at the end of World War II.