View: US Presidential Election 2020, make America connect again

This article was originally published on The Economic Times

At the time of writing, many holding their breath regarding the result of the US presidential election recognise the relative stability and prosperity of a global rules-based system upheld through multilateral collaboration. They sense that a collaborative system safeguarded and guided by the US, despite its past failings, still holds promise. With the threat of Covid-19, nuclear proliferation, climate change and a trade war, it’s inevitable to ask what today’s election outcome will hold for US foreign policy, and for any hopes of coordinated global governance.

Trump largely stuck to his ‘America First’ approach during his first term. Under his administration, the US has withdrawn from major international agreements on climate, arms control and Iran, as well as pulled out of UN human rights bodies, renegotiating trade deals, implementing restrictions on immigration and igniting a tariff battle with China. All this has resulted in a weakening of core alliances and cutting ties with neighbouring countries.

Should Trump win a second term, in his eyes, the US public will have provided a mandate for his go-it-alone foreign policy. This would likely mean further inaction on climate, downplaying Covid-19 and the rising threat of nuclear proliferation. When it comes to China, presumably Trump will neither tone down his criticisms of the country’s economic and human rights abuses, nor his narrative placing blame for the Covid-19 pandemic squarely on Beijing’s shoulders.

But despite everything, it’s not impossible to imagine that Trump could come to see the costs of severing transnational alliances. In another four years as president, he may realise that international fora and a rulesbased system take some of the burden off leading nations, while deterring aggressors. Many second-term presidents bear the brunt of their first-term decisions as longer-term consequences catch up. Moreover, without the constraints of a re-election campaign, he may find it easier to trade headline-grabbing tactics for greater practicality.

It’s also plausible to consider that Trump’s political power during a second term may decline, as it’s no sure bet that Republicans will hold the Senate. With a Democrat-controlled Senate, Trump’s repudiation of global multilateralism and cooperation will face strong objections. In the end, one hopes that Trump — a consummate ‘pragmatist’ in the eyes of his base — comes to realise that playing the role of leader in a global, multilateral system affords one immense opportunities to shape the nature of those rules.

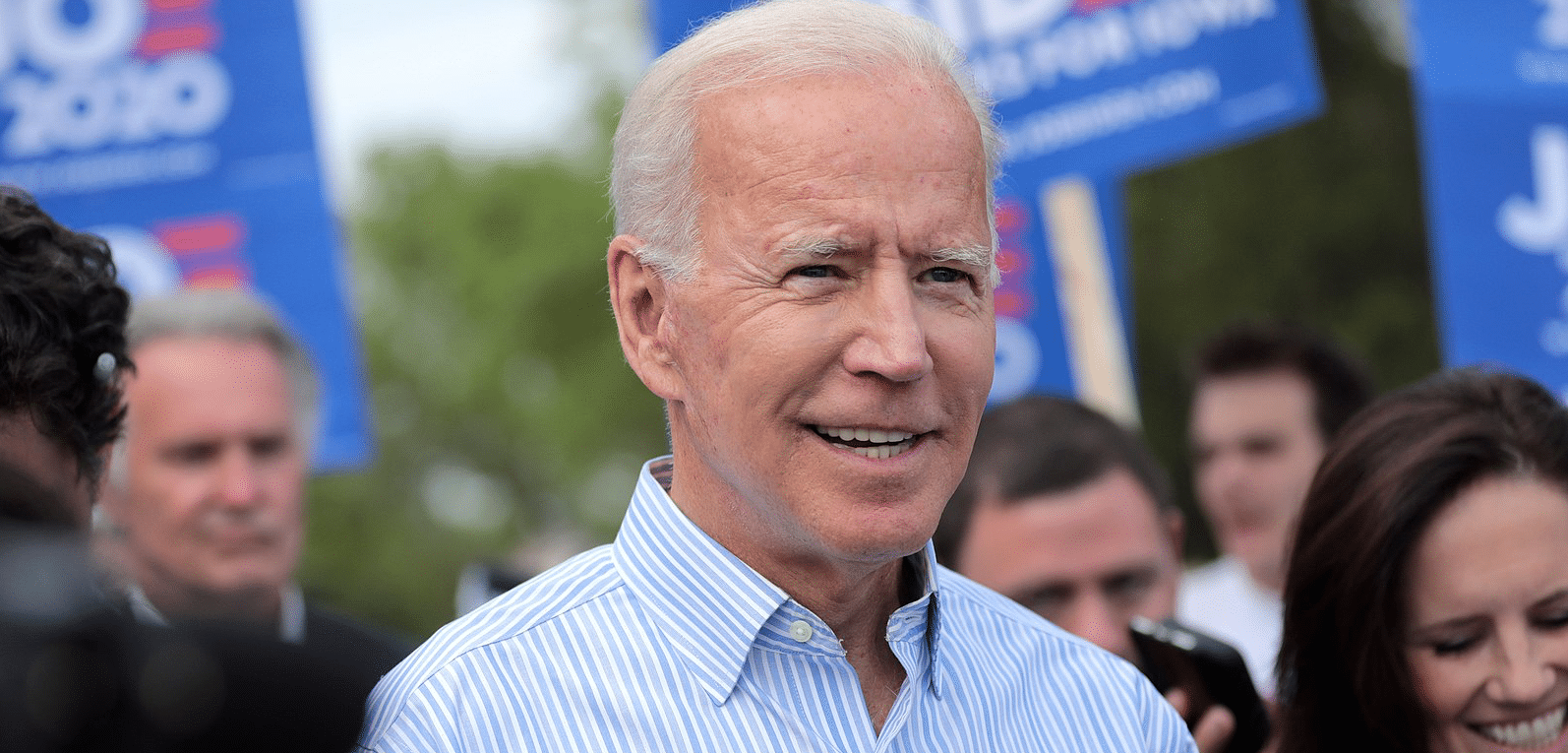

If Biden comes to the Oval Office,he brings with him years of foreign policy experience as chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and two-term vice-president of the Barack Obama administration. He understands what it means to lead on the international stage. During his presidency, one can expect to see a decisive pivot away from Trump’s policy on Covid-19, climate and international trade rules. While Biden’s approach to trade deals may prove more sceptical than that of previous administrations, any actual reluctance will likely be based on a commitment to domestic recovery, and a distaste for deals that will appear to drive inequality. One can also hope a Biden presidency means quick action to restore order on multiple fronts and rebuilding bridges burned by Trump.

Biden could promote reforms that ensure more accountability for authoritarian leaders, and trade rules that don’t push those at the bottom of the economic ladder further down the rungs. His desire to renegotiate the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), for example, may signal a commitment to making free market economics work better across the board, rather than rejecting them outright.

The most consequential foreign policy matter hanging in the balance is the volatile relationship between the US and China. If Trump is reelected, he is likely to continue down the path of economic and political decoupling with China. But we’d be wrong to expect that a Biden victory would trigger a much less confrontational stance towards China. Biden has been vocal on China’s persecution of its Uighur Muslim population, unfair economic practices and intellectual property (IP) theft. Pressure to be tough on China has also been mounting within the Democratic Party.

On many key points, Trump and Biden are actually in agreement on China. A President Biden may well keep some existing penalties against Beijing in place, restrict Chinese imports or even use Trump’s tariffs as leverage against China. But even in this context, Biden’s tactics are likely to be far more multilateral in nature. We can expect him to look to allies for cooperation in jointly pressing China, while simultaneously cooperating with Beijing on vital matters such as climate change and global health security.

Most Americans seem to hold out hope for a world that’s not splintered by multipolarism. Most — including seven out of 10 Americans surveyed by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs (bit.ly/387mg5B) — believe that a US return to a more active role in world affairs will be beneficial in the future. But with existential crises looming, political antagonism mounting and isolationist sentiment prevailing, the future does not look bright if the world is resigned to toss out multinational institutions and global governance, instead of seeking to fix them. The world will also be in trouble without American leadership.