Winning Back Our Voices: Solutions to Voter Suppression in India

Voter Suppression is any legal or extralegal measure or strategy whose purpose or practical effect is to reduce voting, or registering to vote, by discouraging or preventing members of a targeted racial group, political party, or religious community from exercising their right to vote, in order to influence the outcome of an election. It attempts to reduce the number of voters who might vote against a party or candidate, by either purging names of registered voters from electoral rolls, or creating hurdles for new voters to register or registered voters to vote. Minorities are usually disproportionately affected by this phenomenon that occurs world-wide.

Why is this an Indian problem in need of immediate attention?

1) Voter suppression is against the spirit of articles 324-329 (Part XV) of the Indian Constitution; article 324 mandates that the Election Commission ensure free and fair elections, while most significantly article 325 mandates that no eligible voter shall be deprived of his or her right to be on the ballot roll for their constituency. Articles 325 and 326 provide the basis for the Representation of People’s Act (1950). Both articles and the act also lay down the procedure for deletion of names from electoral rolls, and establish that no names can be deleted from the roll except in accordance to aforementioned procedures.

2) Alienation from the electoral process takes away a vital instrument of empowerment from the most oppressed; the former ‘BIMARU’ states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar saw a churning of backward castes and classes post the Mandal Commission phase in the 1980s and after. Parties representatives of the OBCs and SCs managed to win the seats of power in these states with rampant caste discrimination and finally assert the true power of their communities. This process was made possible by the mobilization of a passionate electorate and their ability to cast their vote. This was the first and, in several aspects, the only way by which some of these communities could empower themselves. If they are disenfranchised from the electoral process, they lose the most vital instrument to their empowerment.

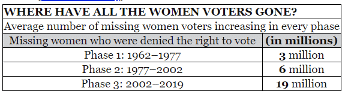

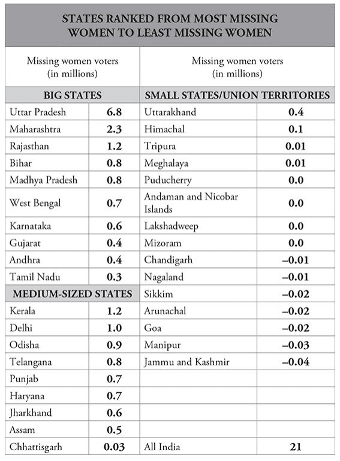

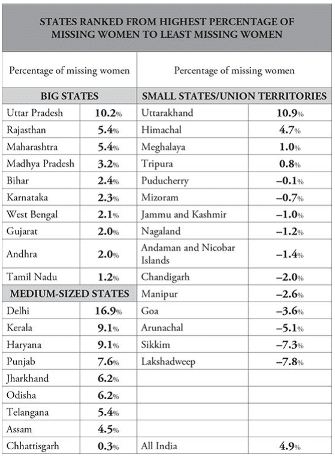

3) It can swing the vote. Prannoy Roy and Dorab Sopariwala’s analysis of the 2019 Lok Sabha election in their book ‘The Verdict: Decoding India’s Elections’ revealed approximately 21 million women to be missing from the electoral roll, which averages to 38,000 per constituency. Given that approximately one in five constituencies are won by margins smaller than this, it is possible for such an omission to swing the vote, especially considering that women are a vital votebank in several places, where they often vote independently from their families.

Source: Table 1.2.14 Roy & Sopariwala (2019). ‘The Verdict: Decoding India’s Elections’

Source: Table 1.2.15 Roy & Sopariwala (2019). ‘The Verdict: Decoding India’s Elections’

Source: Table 1.2.16 Roy & Sopariwala (2019). ‘The Verdict: Decoding India’s Elections’

In Uttar Pradesh, the average came to about 85,000 missing women per constituency. An Opinion Poll by the Hansa Research Group for NDTV revealed that in the 2014 election, male voters formed the bulk of the NDA votebank; if only the male electorate was counted, the NDA would’ve won 336 seats, whereas if only the female electorate was counted, the NDA would’ve been down to 265 seats.

4) It discourages increased voter participation and encourages voter apathy. Voter suppression can result in targeted voters feeling “estranged or disaffected from the system or somehow left out of the political process.” due to legal or logistical barriers or encountering registration problems, which cause feelings of indifference towards the electoral process. This discourages them to vote and leads to lower voter participation and thus turnout.

5) Gaps in the system that cause voter suppression can be exploited by political parties for targeted disenfranchisement of hostile voters. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, the BJP in Karnataka alleged that upto 2 lakh voters were deleted from the electoral rolls in Bangalore in a deliberate attempt to dent its vote share.

The Problems

India is the largest democracy in the world, that with 90 crore eligible voters in its last election, including 15 million first time voters (18-19) hold the world’s largest elections, it is thus crucial to understand what challenges lie in our path to eradicating voter suppression and making our democratic functioning as smooth and fair as possible.

1. Misuse of Form 7

Form 7 is an application for voter deletion. A brief case study of a purge of the electoral roll that took place in Andhra Pradesh in March 2019 has revealed the possibility of its misemployment to indiscriminately delete voters.

YSRCP’s Jaganmohan Reddy claimed that the state’s electoral roll included upto 58 lakh bogus and duplicate voters, while the TDP hit back by stating that the YSRCP was attempting largescale deletion of TDP voters by use of form 7s. The YSRCP admitted that they did indeed submit Form 7’s, but only where in their opinion there were duplicate or double entries.

AP police registered over 45 FIRs across the state based on complaints made by the State Election Commission. The SEC admitted to the media that attempts had been made to delete voters en masse by sending Form 7 on their behalf without their permission. According to reports, the ECI received approximately 8 lakh forms, requesting deletion of voters.

Filing Form-7 online is a simple process needing only a voter card or EPIC numbers, that can be filed by anyone on behalf of the voter. Alarmingly, the EC does not inform or communicate to the voter at all that a request for voter deletion has been received in their name, and the only security feature of the online form is captcha.

The EC’s primary roll in this process of deletion is that of verification, which requires the Electoral Registration Officer (ERO), to whom the letter is addressed, to send a Booth Level Officer (BLO) to personally check if the voter in question is still residing at the address stated on the electoral roll. Based on the BLO’s feedback, the voter is then deleted or retained.

As seen in the AP scenario, this can easily be exploited by political parties with vested interests, to use their own discretion to decide who the bogus voters are.

2. Deduplication software

The National Electoral Roll Purification and Authentication Programme (NERPAP), was the ECI’s questionable attempt using software based on Aadhaar to flag duplicate voters’ names for deletion. The gaps and faults in NERPAP led to the programme being halted in 2015, but its consequences were felt in several subsequent elections –

In 2018, the Telangana Chief Election Officer apologized to the public for deleting names of over 30 lakh voters, several of whom were left wrongfully disenfranchised before the 2018 assembly elections. People complained that their names had been removed without proper verification.

Karnataka deleted 13.8 lakh entries since May 2018, of which 5.05 lakh were in Bengaluru. Officials claimed that these were just fake and duplicate entries, and removing details of voters who have shifted or died, independent surveyors have argued that the proportion of deleted voters in some constituencies would be indicative of a “mass exodus” which wasn’t possible. The BJP cried foul about the deletions claiming they targeted BJP voters, especially in the Bengaluru South constituency.

According to Al Jazeera similar mass deletion of names from voters’ lists has been reported from other states, such as Andhra Pradesh, Uttarakhand and Delhi as well.

3. Difficulty in registering and acquiring a voter ID

One of easiest ways of voter suppression is creating hurdles in voter registration. Indian citizens have frequently commented that the process of acquiring a voter ID is too cumbersome, and there is not enough public awareness about the processes and platforms available to aid them through it.

The Solutions

The last polling exercise in our country, cost an unprecedented Rs 50,000 crore, according to New Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies (CMS), which amounts to roughly $8 spent per voter in a country where about 60% of the population lives on around $3 a day.

These expenses are in vain if they cannot safeguard the right of each and every citizen of our country to exercise their fundamental and inalienable right to vote.

1. Communication of receipt of Form 7

The misuse of Form 7 can easily be curtailed by implementing a system where the voter on whose behalf a Form 7 has been received by the ERO, is informed through text, email as well as post of such a submission.

This will allow voters to exercise their constitutionally guaranteed right to have “a reasonable opportunity of being heard in respect of the action proposed to be taken in relation to him” under Section 22 of the Representation of People Act, 1950.

2. Accountability of BLOs & creation of an Audit Committee

The en masse deletions of voters in incidents such as Andhra Pradesh, suggest either rampant inefficiency or corruption in the Booth Level Officer’s tasked with verifying the accuracy of Form 7s. Such profound mistakes in the conduct of public representatives of the ECI is a blot on the Commission’s integrity, and should not go unpunished. This is the only manner in which voter rights will be safeguarded by officers that are meant to protect it.

A committee by the name of the “Election Integrity Commission” should be set up to create and enforce a rulebook with a clear set of penalties and repercussions for mischief or misconduct by its officers following thorough investigations. The committee should also conduct random checks and audits of people that have been deleted to create fear of accountability and oversight in junior officers. This committee set up by the Law Ministry, should have overseer representatives at the district-level and consist of members of the ECI, civil society, and representatives from all national parties.

A slightly similar model is already being worked on in Karnataka where a committee has been formed to look into the grievance redressal of “missing” voters.

3. Automatic Voter Registration

Automatic Voter Registration is a policy popular in the United States of America, by which eligible voters are automatically registered to vote whenever they interact with government agencies such as the RTO, or other forms of identity cards such as Aadhar cards or ration cards. This makes it easy for voters to register onto the electoral roll, as eligible voters are registered by default, although they may request not to be registered.

In rural parts of the country, linkages can also be made between registration cards of gas connection, employment schemes and other welfare “yojanas” with registration for voter cards to increase accessibility. This policy alongside the ECI’s current recommendation to register students in schools and colleges at age of 17 could increase the number of registered voters dramatically.

Conclusion

The diverse and multicultural social fabric of our nation has stood strongly by the electoral process, and over the decades no coup, revolution, nor collapse has come close to destroying it. With that said, it would be foolish optimism to believe that the process itself is sound and without flaws. Voter suppression, be it due to faults in the system or orchestrated by parties with vested interests, is an alarming problem. Our vision of improving our democratic functioning by welcoming the opinions and recommendations of citizens in March this year, will no doubt champion reform further.

We strongly urge that while looking into issues of voter participation, voter turnout, and voter indifference, the problem of voter suppression also be given its due importance, to ensure that our great country’s elections are not just free and fair, but also the most accurate representation of all the people’s will.

By Tannisha Avarrsekar, Founder, CEO & Editor-in-Chief at Lokatantra, and Siddhant Kesnur, Policy Research Associate at Lokatantra

Tannisha Avarrsekar, Founder, CEO & Editor-in-Chief at Lokatantra

Siddhant Kesnur, Policy Research Associate at Lokatantra