American Nuclear Strategy: Challenge of Mind, not Politics

In human history, the highest achievements of war preparedness and war avoidance can be found in triumphs of intellect, or victories of mind over mind. Today, in an unstable world of growing military nuclearization, major world powers will have to focus their efforts on similar triumphs. This means herculean intellectual efforts, and not variously banal tasks framed by politics.

Credo quia absurdum, said the ancient philosopher Tertullian. “I believe because it is absurd.” We live at a moment where any primary preference for politics over science could prove irremediably lethal. In the post-Trump United States especially, it will be vital to reject a still-pervasive unphilosophical spirit that wants to know nothing of truth. In essence, a nuclear nation mired in conspiracy theories and epidemic anti-reason ought never expect any significant triumphs of “mind.”

How to proceed? To optimize their expressly non-political work, US strategists will need to acknowledge that global anarchy is never just a transient impediment. Rather, since the seventeenth century Peace of Westphalia, which ended the last of the religious wars sparked by the Reformation, anarchy has been deeply rooted in the codified and customary foundations of world politics. Now these legal and geopolitical structures point to still-expanding conditions of chaotic regional disintegration.

Yet, even in chaos, there can be a discernible system. Accordingly, there can be no compelling argument for examining current and future threats to US national security as if each threat were singular, unrelated or detached. Always, there are certain foreseeable interactions between individual harms, or synergies. These interactions could make the potentially existential risks of anarchy and chaos more pressing and potentially catastrophic.

Anarchy and chaos are now more portentous than ever before. This enlarged vulnerability owes largely to the unprecedented fusion of a continuously decentralized world politics with apocalyptic weaponry. “Man’s heart is in his weapons,” warns the devil in George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman, “in the arts of death he outdoes Nature herself.”

There are prominent current examples. In the United States, the head of STRATCOM, the country’s top nuclear commander, mused openly about deterioration of America’s strategic triad. Admiral Charles Richard worried that the aging Minuteman III ICBM force could soon be abandoned, and that a problematic US bomber force would need to take its place as the always-ready leg of America’s nuclear deterrent. For the moment, only the missile-bearing submarines and ICBMs are “ready to go.”

Russia has its own nuclear triad; China is progressing along similar strategic lines. Today, says Admiral Richard, what you have in the US “is basically a dyad.” In 2017, the Department of Defense announced that the USAF was preparing to put back nuclear bombers on 24-hour alert, but this vital step was never actually taken.

Will America allow itself to be guided once again by starkly vacant political rhetoric and presidential bravado, or instead base its nuclear strategy on considerations of “mind”? In a worst case scenario, circumstances will obtain where there could be no safety in arms and no rescues from political authority. In time, recurrent wars would rage until every flower of sustainable culture was trampled and all things human leveled in primal disorder.

Since the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, our anarchic world can be described as a system. What happens in any one part of this interconnected world necessarily affects what happens in some or all of the other parts. When a deterioration is marked, and begins to spread from one nation-state to another, the chaotic effects could undermine regional and international stability. What then?

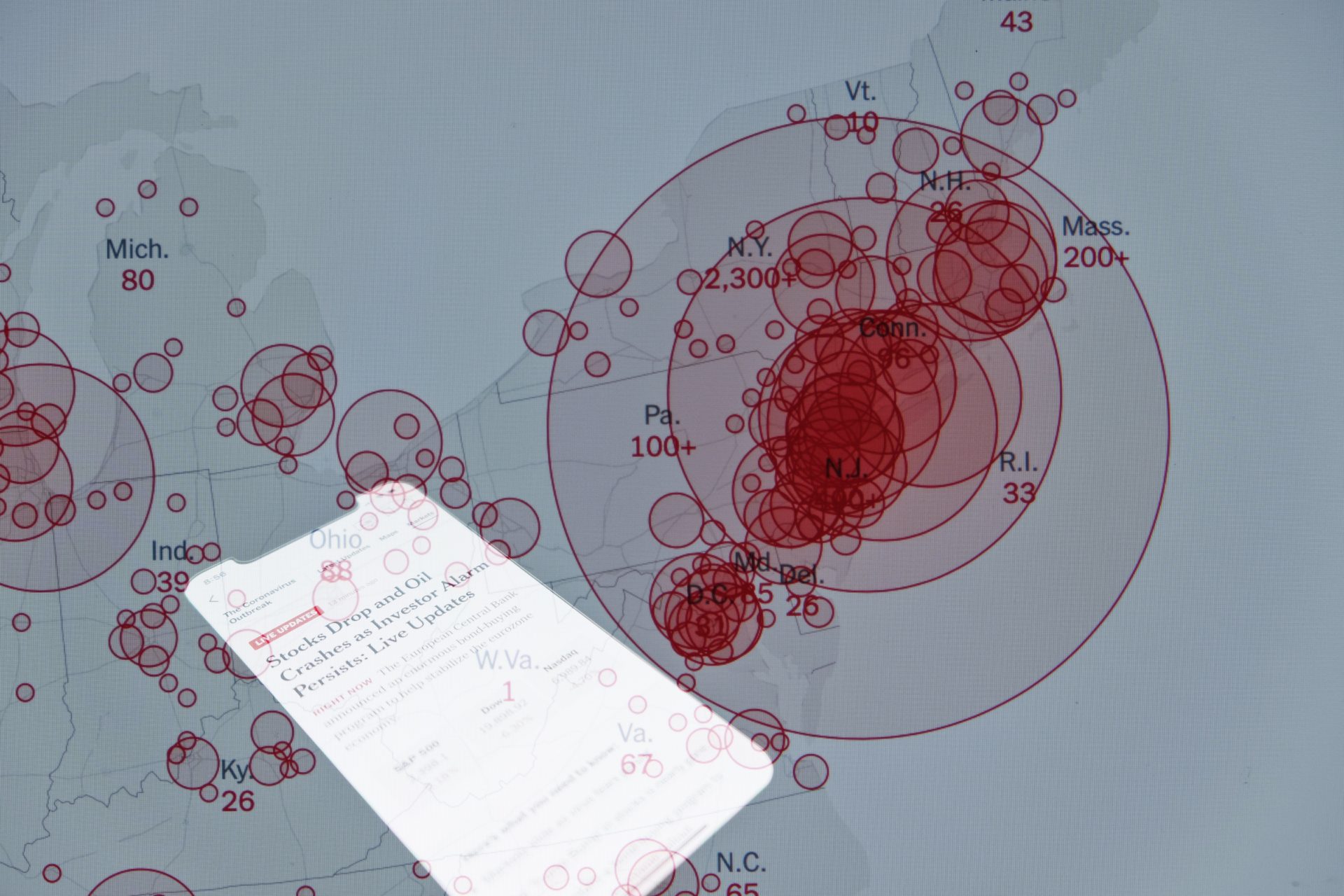

Looking beyond Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan and mature political philosophy that formed the wellspring of America’s founding documents, the specific triggering mechanism of the world’s plausible descent into chaos could originate from mass-casualty attacks of several sorts; a mass-dying occasioned by disease pandemic or assorted synergies arising between these causes. Alternatively, it could draw explosive nurturance from the belligerent use of nuclear weapons in seemingly distant regions. If, for example, the first military use of nuclear weapons after Hiroshima and Nagasaki were initiated by North Korea or Pakistan, Israel’s nuclear survival strategy could have to be re-conceptualized and aptly/amply modified.

The “spillover” impact on the United States of any nuclear weapons use by North Korea or Pakistan would depend, at least in part, upon the combatants involved, the expected rationality or irrationality of these combatants, the yields and ranges of nuclear weapons actually fired and the calculated aggregate numbers of civilian and military harms. These calculations would all be intellectual, not political.

There is more. The State of Nations remains the State of Nature. For Americans, the expected fragmentations in post US-withdrawal Afghanistan would represent just a beginning. Here, wider patterns of anarchy, chaos and disorder will be more-or-less inevitable. All that might then still be avoided by proper inputs of “mind” is mega-destruction. Such avoidance would not be insignificant.

In all science-based strategic assessments, there are variables that will remain refractory to measurement, but still be of explanatory importance. At some point in our dissembling age of chemical, biological and nuclear weapons, the consequences of assorted strategic planning failures spawned by politics could become overwhelming. The only foreseeable remedy for such intolerable failures must be a prior national focus on science and “mind.”

Some further calculations will be needed. A rational nation-state enemy of the United States will always accept or reject a first-strike option against this country or allied states by comparing the costs and benefits of each alternative. Where the expected costs of striking first were presumed to exceed expected gains, this enemy would be deterred. But where these costs were believed to be exceeded by expected gains, deterrence would fail. Here, an American ally could be faced with enemy nuclear attack, whether as a “bolt from the blue” or as the outcome of crisis-escalation.

A tangible example would be a crisis in northeast Asia involving North Korea and US security guarantees of “extended deterrence” to South Korea and/or Japan. Here, in extremis atomicum, states vying for “escalation dominance” could unwittingly find themselves in midst of an uncontrollable nuclear war.

The single most important factor in science-based judgments on preemption would be the expected rationality of enemy decision-makers. If these leaders could be expected to strike the US or a US ally with nuclear forces irrespective of anticipated counterstrikes, deterrence would cease to work. This means that certain enemy strikes could be expected even if the enemy leaders fully understood that the US and/or US ally had “successfully” deployed its nuclear weapons in survivable modes; that its nuclear weapons were believed to be capable of penetrating the enemy’s active defenses; and that leaders were conspicuously willing to retaliate.

“Everything is very simple in war,” says Carl von Clausewitz in On War, “but the simplest thing is still difficult.” For America, this means an overriding obligation to forge, dialectically and deductively, sound strategic theory. More precisely, this would be a coherent network of interrelated propositions from which suitable policy options could be identified, rank-ordered and scientifically selected. These would be matters of decision for “mind,” not politics. In these matters, we should learn from earlier US presidential politicization of urgent medical matters.

For the United States and the wider world, no subject could be more conspicuously important than nuclear strategy, a subject that will never yield to the narrowly visceral intuitions of domestic politics. Going forward in the current Biden Era, America must return to an earlier post-World War II awareness that any such subject warrants a response that is self-consciously intellectual. To be sure, recalling Donald Trump’s incoherent presidential promises regarding both North Korea and Iran, intentionally simplistic phrases of common political discourse would appear reassuringly “softer.” Inevitably, however, such disingenuous palliatives (analogous to claiming that a grave pandemic disease will “disappear on its own”) would prove stunningly foolish and gravely wrong.

LOUIS RENÉ BERES, a regular contributor to Horasis, was educated at Princeton (Ph.D., 1971); he has lectured and published widely on world security issues and international law. Born in Zürich, Switzerland on August 31, 1945, he is the author of twelve books and several hundred journal articles and monographs in the field. Dr. Beres’ pertinent writings have been published in Israel Defense; The Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs; Parameters: The Official Journal of the US Army War College; International Security (Harvard); Special Warfare (JFK Special Warfare Center, U.S., Army); International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence; Strategic Review; Israel Affairs; World Politics (Princeton); Military Strategy Magazine; Harvard National Security Journal (Harvard Law School); Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists; Armed Forces and Society; JURIST; Oxford Yearbook of International Law (Oxford University Press); Yale Global; Comparative Strategy; Journal of Counter Terrorism and Security International; NATIV (Israel); The Hudson Review; Policy Studies Review; The Jerusalem Journal of International Relations; Political Science Quarterly; e-Global (University of California); International Journal; Philosophy and Social Criticism; The Journal of Value Inquiry; Cambridge Review of International Affairs (Cambridge University); Dissent; The Review of Politics; The American Political Science Review; Policy Sciences; The War Room (Pentagon); Modern War Institute (Pentagon); and Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. Professor Beres has also published on timely strategic matters in several dozen law journals, law reviews and various monographs published by the Ariel Center For Policy Research (Israel); The Joan B. Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies (University of Notre Dame); The World Order Models Project (World Policy Institute, New York and Princeton); The Monograph Series in World Affairs (University of Denver); and The Graduate Institute of International Studies (Programme For Strategic and International Security Studies, Geneva, Switzerland). His monographic publications in Israel have been posted with IDC Herzliya; BESA Center for Strategic Studies; and The Institute for National Security Studies, Strategic Assessment. His newest book is titled Surviving Amid Chaos: Israel’s Nuclear Strategy (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016). (2nd ed. 2018). https://paw.princeton.edu/new-books/surviving-amid-chaos-israel%E2%80%99s-nuclear-strategy