The Future of Economies: Inflation, Deflation, or Stagflation?

The current macroeconomic climate is one characterized by uncertainty as the well-established rules around global trade and services are being rewritten, and forces from climate change to war shake the foundations of economies. These issues are the result of years of disruption and upheaval, with some pointing the COVID-19 pandemic as the start, while others consider this the natural evolution of decades of globalization.

There are solid arguments for COVID-19 being the most impactful event of this generation, as research suggests that the pandemic pushed the world economy back by 5-10 years. COVID-19 has widened gaps between the rich and poor and curtailed the SDG achievements of the world’s poorest countries, resulting in a “lost decade of development.”

Geopolitical rivalries are also rewriting the dynamics around global trade, which in turn is slowing down global growth. Following US President Trump’s recent tariff announcement and widespread uncertainty around the trade policy of the world’s largest economy, global markets and international trade have revolted. Earlier this year, the OECD slashed global GDP growth to 2.9% from 3.1% for 2025 and 2.9% from 3.0% for 2026, with the US, China, Canada, and Mexico expected to witness the biggest slowdowns in their economic growth.

Climate change also has a direct effect on a country’s economy. An average temperature rise of 1°C in a country, can cause per capita incomes to fall by an average of 1.4%, as temperatures have been found to affect income through agricultural yields, worker performance, energy demands, and incidences of crime, unrest, and conflicts.

So, what are all these issues amounting to? Many economists are considering what state these forces will leave the global economy in—are we heading to inflation, deflation, or stagflation? It is too early to determine anything, but what is certain is that the world is undergoing a great period of shock and reorientation, and immediate action is needed to arrest economic freefall.

These are just one of the agenda items up for discussion at the forthcoming Horasis Global Meeting, scheduled to take place in São Paulo, Brazil, between 7 to 10 October 2025. In its 10th edition, the meeting will draw together opinions and experiences of global leaders from various backgrounds on finding cooperative frameworks to our present challenges.

Inflation, Deflation, or Stagflation

Experts are of the belief that economic upheaval brought about by the Liberation Day tariffs could push the US economy to either recession or stagflation—with the latter being a more worrisome concern. Unlike recession— where unemployment rises while the prices of goods drop—stagflation is a rare phenomenon with a combination of economic slowdown and rising inflation.

Some prominent voices think this is likely to happen. According to JPMorgan & Chase CEO Jamie Dimon, the odds of US being hit by stagflation is roughly double that of market expectations.

How this plays out may also vary from country to country. In China, the government’s decision to divert US-bound exports to its domestic market may push the country into deeper deflation. This move has already strained the existing weak domestic demand in China, triggering intense price wars, reduced profit margins, payment delays, and high return rates. Deflation will hit companies hard in the mid-to-long term, forcing businesses to either cut down on wages or employees. This is expected to impact 16 million jobs, reflecting the fact that 2% of China’s workforce is involved in the production of US-bound goods.

Meanwhile in Europe, the bloc has responded to the economic uncertainties brought about by the Russia-Ukraine war and Trump’s tariffs by cutting interest rates and boosting spending on defense and infrastructure. This has yielded some positive effects, with inflation across the 20-member eurozone falling to 1.9% in April 2025—an improvement from European Central Bank’s target of 2%, and an achievement that many expect to stick around for the next few years.

Economic Theories Offer Response

Why does it matter how we diagnose the economy?

While many of these issues may not be understood by the average lay person, the fact is that economic theories can help nations respond to these emerging crises. Historically, old school of economic theory believed in the self-correcting forces of the market economy, arguing that the market will self-regulate in economic crisis.

This theory was challenged in the 1930s during the Great Depression by John Maynard Keynes, who stated that governments need to intervene during economic crises to stabilize the economy. The Keynesian school of thought promoted an increase in government spending on labor-intensive infrastructure projects to stimulate employment and stabilize the economy, while reduce interest rates to encourage investment. In the 2007-08 Global Financial Crisis, this theory was widely used as the basis of policy response by many governments, including the US, who saw its economy recover quickly in the aftermath.

But Keynes economic theory has limitations to appropriately respond to stagflation. In the 70s, the US learned the hard way that fiscal and monetary policies can be immune in the face of stagflation.

At the moment, US Federal Reserve has chosen to hold raising interest rates due to grave uncertainty looming around US President Trump’s tariffs strategy and his broad economic policies. How these decisions will play out remains to be seen.

While each country will have their own response to the current challenging economic climate, that doesn’t mean they should retreat further into isolation. In fact, the challenge facing the global economy requires a collective response. The pandemic helped prove that.

What we need to ensure resilience is collaboration, not only from global leaders but also multilateral organizations, businesses, and public agencies. By joining forces and leveraging the power of collective response, we can chart a pathway to recovery and stability.

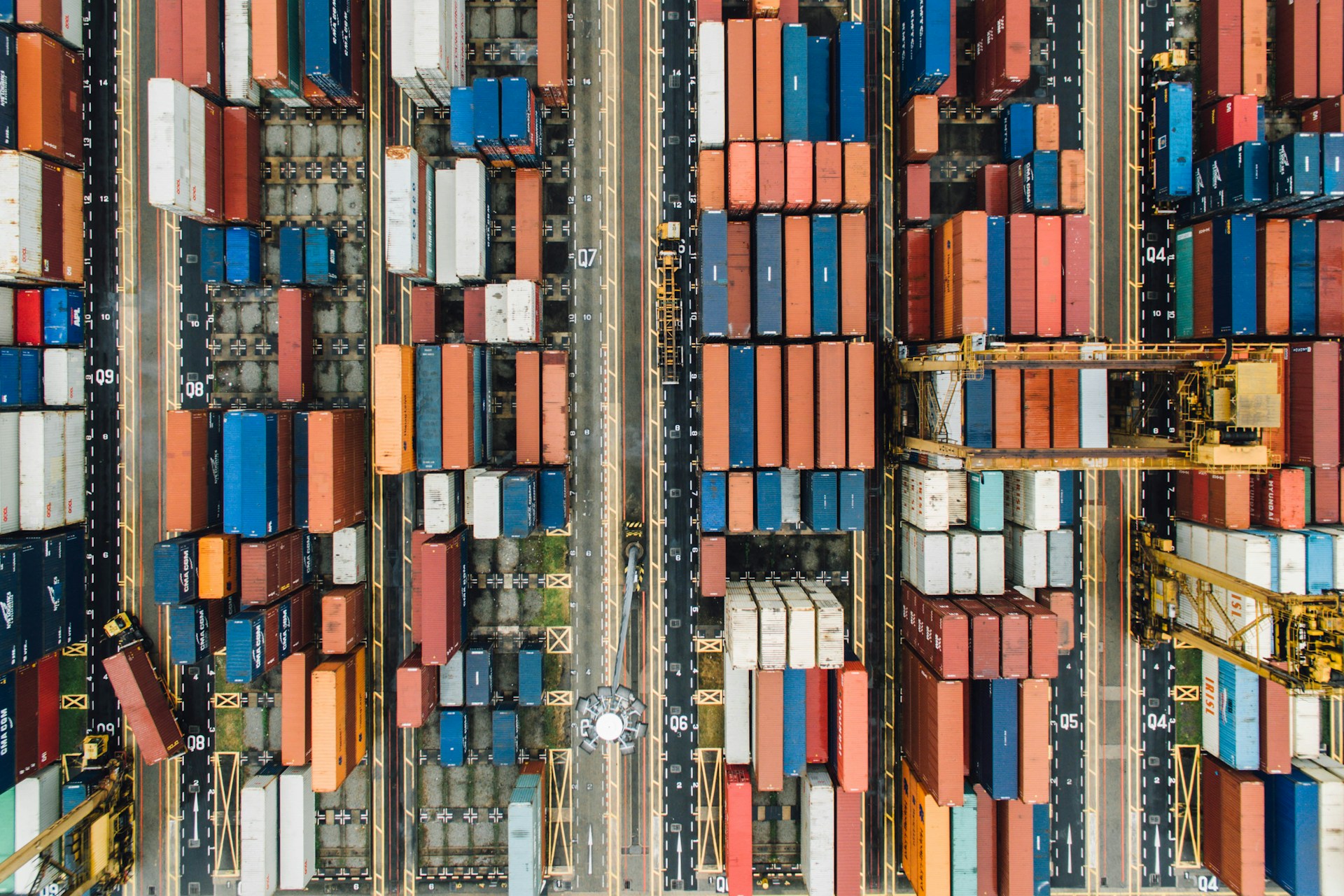

Photo Caption: Shipping containers at a port.