The Three Necessary Pillars of Future Human Well-Being

We consider there to be three interconnected pillars that will go a long way towards our global survival while still maintaining our natural cultural diversity. These are (a) to prepare for the next pandemic; (b) to renovate and develop all infrastructures; and (c) to develop our ability to research deeply and to innovate. Further, to promote this discussion, by ‘we’ I mean to include all national leaders, leaders of civil society, business leaders and ultimately “we” – the people. All must be engaged in these processes from now into the future – let me explain further.

Prehistoric sites have been found across the globe that indicate rapid mass burials followed by cleansing fire: Athens suffered in 430 BC, and the Romans suffered a plague in AD 170. The causes are many, but they resulted in a rapid rise in deaths. In recent times we have seen the influenza pandemic of 1918 killing maybe 50 million people globally, though there was an earlier outbreak in 1889 killing a million bursting out in Central Asia, Canada and Greenland aided by modernized transport systems and an increase in city dwelling. More recently there was HIV/Aids at its peak on 2005-2012; the ’Flu of 1969; and the Asian ’Flu of 1956-1958.

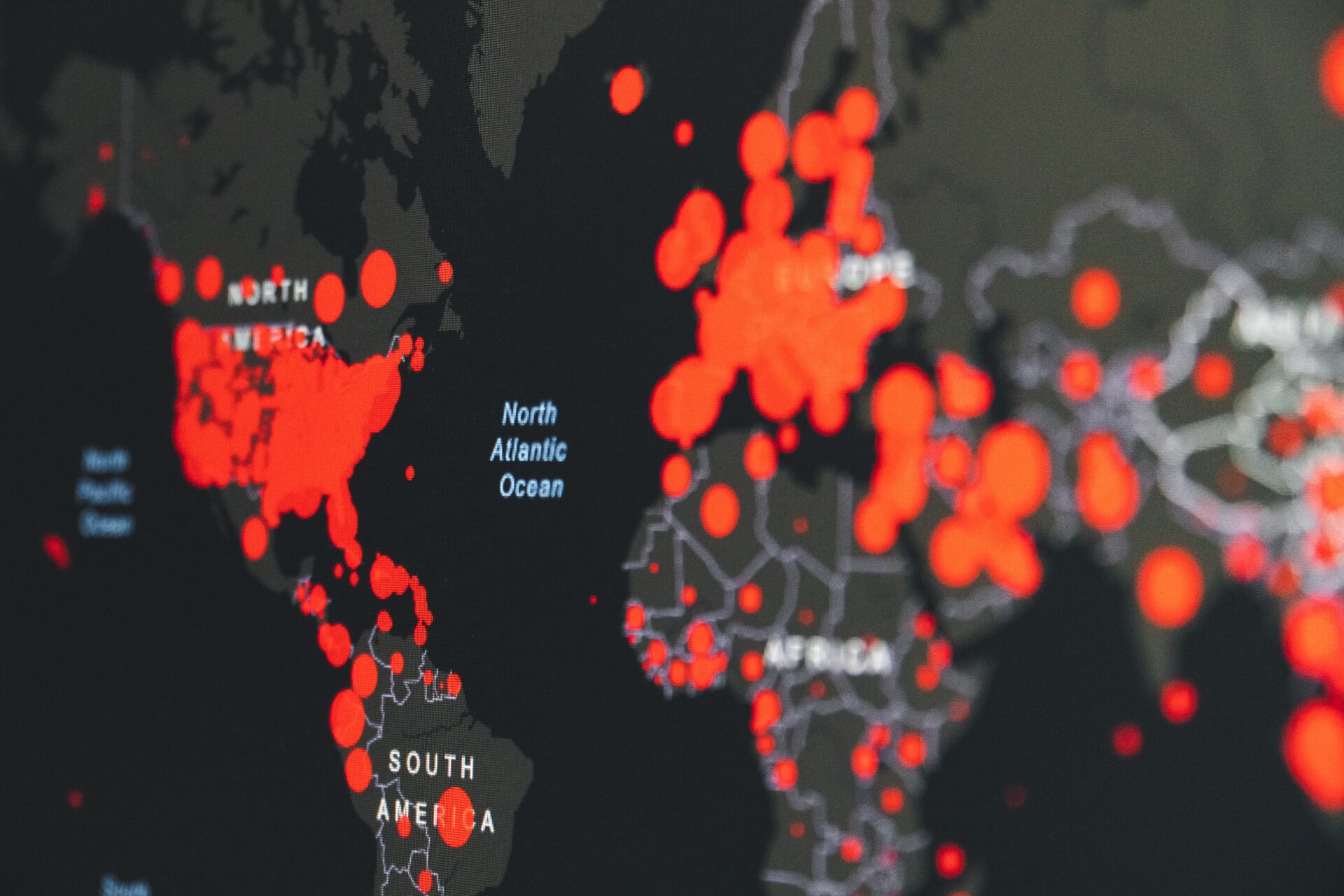

We have not been exposed to an unknown pandemic like the novel Coronavirus, COVID-19 (SARS-Cov-2) for many years even though in many nations it looked as though local virus outbreaks might move on to be multi-point then globalized outbreaks – such as Ebola, the SARS and MERS outbreaks, and the H1N1 virus that spread quickly.

While we all suffer annually from the winter influenza virus that constantly mutates, travelling incessantly from the northern hemisphere to the southern and back again and it seems its virus cure remains elusive there is a great need to be protected from future pandemics. Larry Summers and his mainly economics and finance expert’s panel appointed by the G-20 group of leading rich and developing nations say we need to spend about $15 billion per year in additional funds as well as overhaul the world’s health governance infrastructure. Essentially, they propose four areas – prevention, preparedness and response (PPR), global surveillance, creation of resilient health systems and ensuring a supply chain of essential medical supplies. In addition, a new form of coordinated global governance should be created – a Global Health Threats Board – to supersede the current fragmented groups with it having sufficient funding that ensures coordination. This new Board will bring together global Health and Finance ministers and heads of regional organizations.

The panel noted that the present COVID pandemic has returned millions into poverty, killed an estimated 4 million people, and incurred cumulative losses of about $22 trillion. In contrast, they suggest an annual investment of $15 billion per year (initially over five years) of additional funding for health care in its widest definition. This will be a small fraction of what governments have lost already to the pandemic – but the future results will be seen in stellar economic growth in the trillions of dollars that will be measurable, with immeasurable growth in human wellbeing.

Such a change in global governance will not be easily given there are 92 nations defined as low or middle-income economies who have few resources and see only a future of great suffering. They are one of the difficulties in the next two proposals: first, how will they pay and contribute, as we need to boost all infrastructure repairing, operations and extension. Further there is a definition issue as ‘infrastructure’ is often seen as only bridges, roads and railways and ports: in essence, only transportation. US President Joe Biden has opened this discussion highlighting a strongly resisting US Republican Party who only accepts the narrow definition of infrastructure, while we agree with President Biden on the wider definition that includes services like clean and foul water, electricity, telecoms and even financial services, and also the more human infrastructures of food security, health and its insurance, and education.

If the world does not have well educated people who will develop the transportation infrastructure that the rest of the economy depends upon? Given the present need to accept proposals that incorporate climate change mitigation is will be necessary to project cross-border plans to share and distribute resources – some nations have abundant water but lack electricity, others have wind power that could be exported. And national electrical power management could be extended to handle the sunlight better, switching power routing as night falls in the east to the increasing morning demand in the west, or exporting power north from the deserts in the south.

The industrial revolution rapidly accelerated the greater use of transportation networks on land and at sea and their foundations need to be repaired soon. And like the concept of a pan-continental electricity grid, terrestrial transportation needs to be eased of political restraints such as physical border blocks (like no rail lines) and endless paper-work. These changes are happening, but not quickly enough in reality as nationalism is a globally strong force.

Infrastructures, in other words, need to be integrated. Demographics can inform of the needs for schools, but why forget to train the required teachers? And to develop early-years health services for the benefit of children and parents? The world is beginning a drift to a lower population though longer living, thus educated and healthy people will be desperately needed, free from the ravages of future pandemics. The slow changes in demographics illustrate the grand long-view of our proposals – they will take years to generate observable results as meshing new structures requires thoughtful and trusting compromises.

Given we will be rebuilding our infrastructures the better educated will be in a position to innovate. This is out third point – for without blue-sky research, innovation, and the entrepreneurial application of new features presently unknown, we will not survive. New futures will surface new problems and early research, maybe placed on a shelf as being initially thought to be unapplicable might create the basis of an early cure. That has been seen through the rapid development of COVID vaccines. The normal timescale of medical developments can be counted in decades as many safety tests must be undertaken. But for COVID, three decades of research had been done on the nRNA messenger vaccine that made sense theoretically but had to be made to work for real, then be tested for human safety before it was allowed into people’s arms. Once assessed and certified it could be made at scale – but still not in sufficient volumes for all people, especially those in the 92 low and middle-income economies.

Innovation is not only about vaccines or health but across all aspects of terrestrial and even space research. Research is costly to support and all proposals of change will have to incorporate climate change mitigation and the aspects of the UN’s sustainable development goals. We suggest that we must learn to trust the other – to share costs, to share results. In fact, we would suggest that trust is the fourth and the most basic of the supports needs of the future. Without a renewal of global trust – between individuals, between traders and between nations we will not achieve the full potential of the three developmental pillars. Trust is the hardest to achieve and must not be forgotten.